A few months ago, I fell into a rabbit hole.

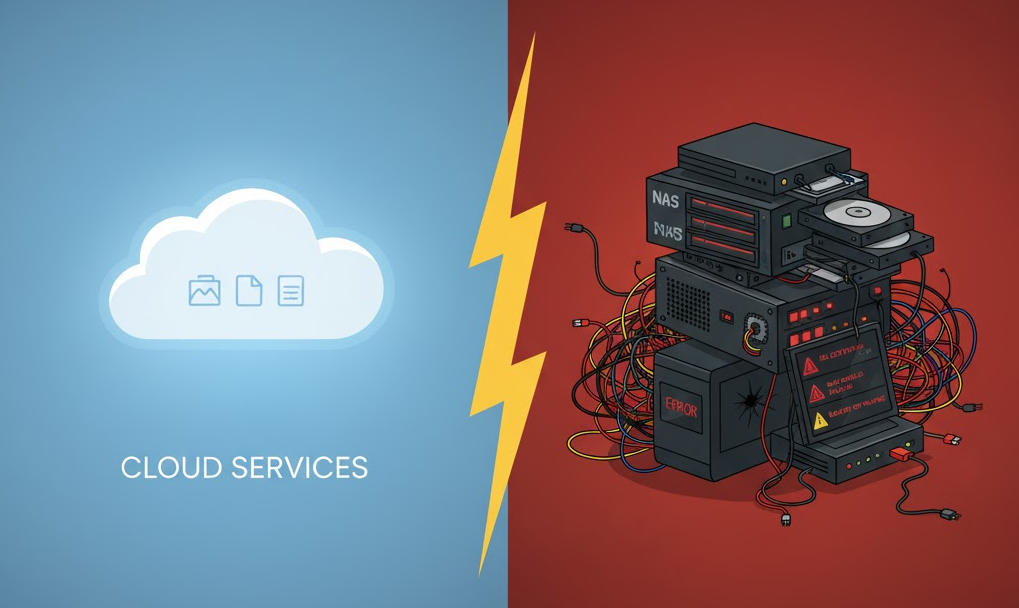

Everywhere I looked, people were talking about self-hosting: replacing Google Photos, Drive, Dropbox, Netflix, Spotify - everything - with a private server at home.

The slogans were bold:

“Digital sovereignty.” “Your data, your rules.” “Big Tech is evil.”

And somewhere inside me, a voice whispered: Maybe I should do it too.

Because the idea is seductive: a personal cloud, fully under my control, performance-optimized, tuned exactly the way I want it.

So I started researching. Not casually - methodically. Comparisons, documentation, benchmarks, long-form technical deep dives. And eventually, as any responsible engineer would do, I opened a spreadsheet.

I ran numbers:

- cost projections

- MTBF for different drives

- watt consumption

- long-term TCO projections

- failure scenarios

This was no longer curiosity. It was an engineering evaluation.

My research branched into real architecture questions:

- Nextcloud vs Google Drive

- Immich for photo recognition and indexing

- Jellyfin vs Plex for transcoding and media serving

- Synology vs TrueNAS vs Unraid (from a maintainability perspective)

- ZFS vs Btrfs checksums and self-healing

- Docker orchestration, reverse proxies, Portainer, firewall segmentation, encrypted backups

I even deployed a couple of Docker stacks locally to observe failure modes when a single dependency broke. It was an instructive disaster.

At one point, my browser had a maze of tabs, GitHub repos, and a NAS sitting in my Amazon cart waiting for the “confirm purchase” click.

I was dangerously close to deploying.

Then I did the thing that separates enthusiasm from engineering: I stopped, stepped back, and evaluated the entire system like I would any production environment.

1. Hardware Reality: The CAPEX Problem

| Component | Estimated Price |

|---|---|

| NAS chassis or mini-server | $300 – $600 |

| 2–4 drives with redundancy | $150 – $500 |

| UPS (critical) | $80 – $150 |

| Cables, cooling, spares | $50 – $150 |

Total upfront: $580 – $1,400

In exchange, I would be replacing services that cost a few dollars per month and currently deliver global redundancy, snapshots, versioning, and near-perfect uptime.

It felt like buying a commercial delivery truck because the subway gets crowded.

2. The Administrative Overhead

YouTube makes self-hosting look like magic: “Just spin up a container and you’re done.”

Reality is closer to production DevOps:

- domains

- reverse proxies

- SSL certificate rotation

- firewall rules

- port forwarding

- user permissions

- encrypted off-site backups

- monitoring

- updates

- dependency conflicts

And when something breaks, there is no SLA. You are the on-call engineer.

This was no longer a fun side project. This was a second job.

3. Security: The Uncomfortable Truth

People claim self-hosting gives you more privacy. But privacy is not a checkbox. Privacy is security.

If I misconfigure a reverse proxy, delay a patch, expose a port, or forget certificate rotation, I am not “sovereign.” I am compromised.

Big cloud providers have:

- 24/7 security teams

- intrusion detection

- immutable snapshots

- multi-region redundancy

- automated failover

My setup would have:

- one router

- one machine

- and a single human responsible for all layers of security

And unless that human has the same expertise as Google’s security teams, “more private” is just a comforting sentence.

4. Backups: The Hard Lesson

If Google loses data, they execute a tested disaster recovery plan.

If my house loses power during a write and the RAID corrupts, my data becomes a memory.

A real backup workflow requires:

- on-site backups

- encrypted off-site backups

- versioning

- retention policies

- integrity checks

- restore testing

Anyone can make backups. Professionals test restores.

I even looked at RAID rebuild probabilities on large drives. If a second disk fails mid-rebuild - a real risk with modern capacities - the entire array can collapse.

At that point, I realized I wasn’t building a server. I was building a long-term source of stress.

5. Uptime and the Spouse Factor

Picture this:

You’re traveling. Someone at home tries to open photos. The server is down.

Phone rings:

“Nothing is loading. Can you fix it?”

Now I’m SSH’ing into a Docker stack from a hotel bathroom, praying the Wi-Fi holds.

Meanwhile, Google runs in New York, Tokyo, Singapore, underground bunkers, and possibly Mars by now. Their entire business is uptime. Mine depends on my ISP and a cheap surge protector.

6. The Final Decision Matrix

Eventually, I built a decision table - the same way I evaluate production trade-offs:

| Criterion | Cloud | Self-Hosted |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability | SLA-backed | Depends entirely on me |

| Cost over 5–10 years | Low, predictable OPEX | High CAPEX + ongoing maintenance |

| Backups | Automatic, tested | Manual forever |

| Uptime | Multi-region, fault-tolerant | Local ISP and power grid |

| Security | Dedicated teams | One human |

| Family Experience | It works everywhere | It works if nothing breaks |

| Cognitive load | Near zero | Constant “what if” mode |

That table ended the experiment.

Conclusion: Certainty Over Sovereignty

I don’t regret the research. It was fun, and I learned a lot.

But it led to a simple engineering insight:

Reliability is not a feature. Reliability is architecture.

It is monitoring, redundancy, failover, disaster recovery, and thousands of invisible decisions that cloud platforms handle for you.

Self-hosting is a fascinating hobby. But as a daily utility, it is inefficient and fragile.

Most people don’t want sovereignty. They want certainty.

Your family does not care where the data physically lives. They care that the photos are still there in ten years.

And for that, the engineering answer is clear: cloud services win.

PS: The Amazon cart is still sitting there. I’m afraid to open it.